I’ve worked on a number of aircraft and parts of aircraft over the past 40 years, but there are a few where I feel that I had a significant role in defining them (or perhaps they had a significant role in defining me). These are what I consider the highlights of my career.

Piper Mojave – This was my first significant design at Piper. When Piper acquired Ted Smith’s Aerostar line, they decided that a variant of the 602P engine installation onto the Cheyenne 1 airframe would make a good replacement for the ill-fated P-Navajo. The plan was a Cheyenne fuselage on a Navajo wing and nacelle, with the 602P’s Lycoming TIO-540 engines. I designed the nacelles. The twin turbo engines from the Aerostar eventually gave way to a single turbo, and extending the basic lines of the Navajo aft nacelle fit around the engine but not quite the engine mount, so I proposed a bulge, similar to a Jaguar E-Type bonnet, over the mount. I tried to duplicate the Aerostar inlets, but ended up with something that didn’t look like either the Aerostar or the Navajo. I think overall it was a nice nacelle – although the intercooler inlet took some refinement in flight test.

The Foster Pod – Piper took an unpressurized Navajo Chieftain fuselage and put it on a turboprop Cheyenne wing and engine to create a commuter aircraft. Unfortunately it didn’t have enough baggage capacity for a commuter, so it was decided to create a baggage pod to fit on the belly. I sketched up an elegant pod but the VP of Marketing came over and said it needed to be bigger, filling the space between the gear and the ground. So I designed something bigger. It wasn’t great, but from a personal viewpoint it was. I designed it, then I got to go down to the shop floor and help to build it and install it on the test aircraft. The entire aerodynamics group (2 people) had resigned for various reasons, so I was asked to replace them and flew in the chase plane during flight test and helped to resolve the issues with separation on the back of the pod. I had designed it in Kevlar/ honeycomb sandwich construction and learned a lot about composites in the process. Since I had performed all the functions from design through analysis and test, people started calling it the Foster Pod, which I really appreciate still.

Starship 2000 – My experience with composites got me a place on the Starship program at Beech working for Duncan Stuart on control surface design. Duncan was a weird Englishman who had designed a yacht in fiberglass, moved onto gliders, worked on the Learfan with Linden Blue, and then moved with him to Beech. He was dedicated to challenging the status quo, and this caused friction with the traditional Beech designers but actually was quite fun.

The Starship 2000 was designed by Burt Rutan. I have a love/ hate relationship with Rutan, because he is able to postulate completely unorthodox solutions to aircraft design, but usually they are crap. In the case of the Starship he created a wildly unconventional design that seriously underperformed. As elegant as it was, it only sold about 50 aircraft, which Beech ended up buying back and destroying. I believe there may be 1 or 2 still out there that escaped captivity.

My composite design experience then got me an interview at Bell Helicopter, who were developing the V-22 tiltrotor. A colleague from Beech got me diverted from the V-22 into Preliminary Design, working for Rod Taylor. Then they formed the Advanced Concepts group under John Sherrer to do Low Observables (LO) and I did that for 7 years.

OH-58X – I did this. Can’t discuss it.

C11X – Bell teamed with McDonnell Douglas to bid on the LHX. There were LO requirements, but since these were classified we couldn’t publicly show any pictures of the concepts. Bell/ McD developed a sequence of public unclassified concepts labelled C7, C8, etc… and my job was to make them LO. I spent about 6 months on and off in Phoenix with a team of LO analysts from McD and me as designer. We came up with our ultimate concept, C11X, but senior engineers ultimately decided to submit a more conventional design with negligible LO treatment. Anyway, Bell/ McD lost to the Boeing/ Sikorsky RAH-66 Commanche, which looked very similar to C11X. It was subsequently cancelled anyway, but if we’d won with C11X maybe it wouldn’t have been…

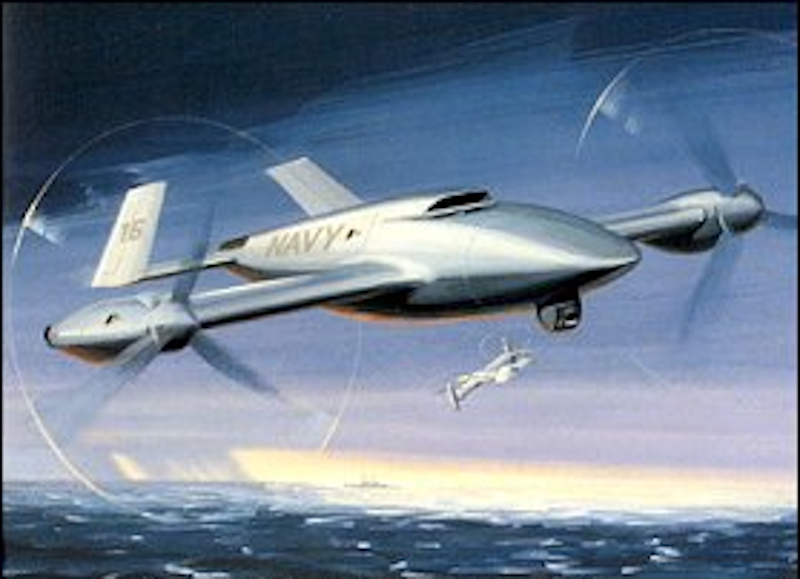

Eagle Eye – Bell had a conceptual high-wing tiltrotor UAV that was a bit lame. It got sent to me to make it LO, and I came up with something like this.

It kinda took off, and we built an unclassified version that’s been flying for a while, but I guess we still haven’t sold any. Shame really, because it really is good.

609 – In early 1994 the VP of Engineering at Bell, Troy Gaffey, was invited to be on a ‘Red Team’ review of the Cessna CitationJet. The CJ was a new, owner-piloted, business jet they were designing. It was small and efficient and Troy cam back to Predesign and asked me to draw an XV-15 (high) wing on a CJ fuselage. I did that, but weight and performance analysis showed that a low-wing fixed-engine design would be more effective. Troy’s response was “If you can’t design an XV-15 wing on a CJ fuselage, I’ll find someone who can”. I led the concept design through collaboration with Boeing and Textron Aerostructures, and moved from the 609 back to Predesign before the partnership with AgustaWestland (now Leonardo). 25 years later, Bell has lost the program to Leonardo and it still isn’t certified. But it will, someday, be recognized as a great aircraft.

QTR – Way back in the 70’s Jack Detore worked on a tandem-wing tiltrotor concept. In the late ’90s we had an idea to mount 2 V-22 wings on a C-130-sized fuselage to make a Quad Tiltrotor. I made a few changes to the original concept that made it fundamentally more practical, such as the stretched aft wing, and we sold it on the basis of 100% commonality in the nacelles with the V-22. After I went to MAPL the project solicited Army requirements that pushed it up in size and lost all the benefits of commonality, ultimately making it unaffordable. I still believe that a QTR that has simply twice the lift of a V-22 would be a winner.

MAPL – In 2002 Troy Gaffey retired and Bell’s parent company, Textron, brought in Milt Sills from Cessna as an interim VP of Engineering. Russ Meyer from Cessna led the aviation group and John Murphy was president at Bell. We had been working on various upgrades to the JetRanger, 407, and 427 for years, and there was nothing that made any sense except a completely new aircraft. We had a plan for a family of aircraft that shared a number of components, with a modular concept. Walter Sonneborn called it MAPL – Modular Affordable Product Line – and John & Milt really picked up on it. Milt asked me to lead the Engineering team. I had some of the best people at Bell, including Paul Griffiths on airframe and Bryan Marshall on rotors, and with Sandy Kinkade in Marketing. I had little experience leading such a large team. We had been given 6 months to complete predesign, and my approach was “I have an idea. I think it is really good, but if you can prove to me that you have a better idea we will go with it.” The combined Engineering and Marketing team did that in a number of ways, and we came up with a brilliant family of 3 aircraft – a 5-place single-engine 3-blader, a 7-place single-engine 4-blader, and a 7-place 5-blader twin-engine.

In 2003 Textron replaced John Murphy with Red Redenbaugh, from Honeywell. He had had good luck with some simple upgrades on the LTS101 engine and thought it was a panacea that would work for us, regardless of the fact that we had extensively investigated upgrades for 10 years. He took everyone off MAPL and put them on upgrades to existing products. Except me. Because of commitments to the Canadian government he couldn’t cancel MAPL.

429 – After looking at all the options to improve the 427, it became clear that the original plan to replace it was the only solution. I worked with the lead engineer on the 427 upgrade program to fit the MAPL fuselage under the 427+ drivetrain, and it became the 429. We persuaded Redenbaugh it was just an upgrade, and the Canadians that it was MAPL (which it really was). The problem is, you can’t really scale it down to the other two.

Since coming to the UK as a program manager at AgustaWestland I’ve been working on components and haven’t had much opportunity to make a fundamental impact to an individual aircraft concept. I do, however, see the aircraft industry changing rapidly again in response to climate change, and some real opportunities being addressed at GKN Aerospace – so watch this space.